Caution: Writer

at Work!

As a professional writer, Arthur C Clarke was methodical and disciplined. He lived by Evelyn Waugh’s words: “If a thing’s worth doing at all, it’s worth doing well.”

Science writer Nalaka Gunawardene, who worked with Clarke for 21 years (1987-2008) as an assistant, recalls:

Sir Arthur’s credo as a writer was to educate, entertain and inspire. His success was due to his remarkable ability to balance these elements in the right proportions.

He sought the economy of words and avoided jargon and bureaucratic terms. He always opted for simple, everyday words. He was fond of saying, “We write to express, not to impress!”

He had an easy and elegant style. He believed in short sentences and short paragraphs. He used metaphors but not archaic ones. He loved to coin a phrase or make up new acronyms. He enjoyed busting popular myths without the arrogance of a know-it-all.

Underlying all this was his deep urge to connect the dots, explain matters and ask the right questions. That is what made him such an amiable tour guide to the future.

“

It was, I believe, Hemingway who said ‘Writing is not a full time occupation’. That’s true in more ways than one. You must live before you can write. And you must live while you are writing. But you mustn’t kid yourself and make excuses to stop work by confusing laziness with that old standby ‘lack of inspiration’. ”

”

– Arthur C Clarke, in 1984 essay titled ‘Writing to Sell’

“

It was, I believe, Hemingway who said ‘Writing is not a full time occupation’. That’s true in more ways than one. You must live before you can write. And you must live while you are writing. But you mustn’t kid yourself and make excuses to stop work by confusing laziness with that old standby ‘lack of inspiration’. ”

”

– Arthur C Clarke, in 1984 essay titled ‘Writing to Sell’

As a writer, he was a perfectionist who would work through three or four or more drafts of any piece of writing until he felt it was just right. He used dictionaries and thesaurus — but not slavishly so. Most of the time the right words came effortlessly, and the prose was then polished further.

Whenever possible, he opted to literally ‘sleep on’ a piece of writing, i.e. put a draft aside for a day or two before returning to it. He always found ways of improving text on such revisits because, he surmised, “our subconscious mind keeps at it”.

Sir Arthur worked hard on his openings and closings. Many of his short stories are known for surprising or highly evocative endings. He also knew the value of having the right title for a book, story or essay and sometimes agonised for weeks looking for the ‘right fit’.

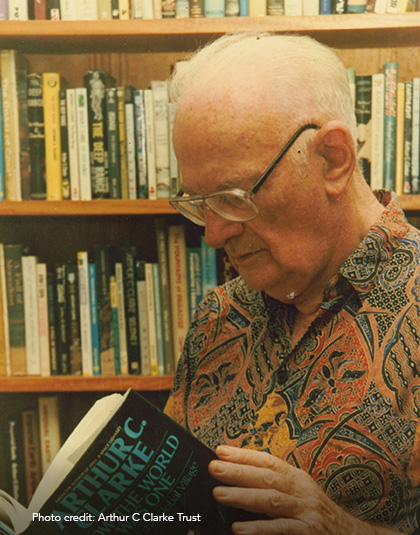

For example, his 1992 book surveying the history of communications was given the title How the World Was One. That summed it up very neatly, even if the English pun could never be translated…

He had a quick wit but was not sharp-tongued. He chose his words carefully, and delivered them in measured tones. In conversation he put down others gently. He never raised his voice to win an argument. If a discussion became too heated or unruly, he turned very quiet – and allowed his silence do the talking. That usually worked.

Haste makes waste, he cautioned us: we had to double check even the most mundane letter sent from his office. He valued attention to detail, but never lost sight of the bigger picture.

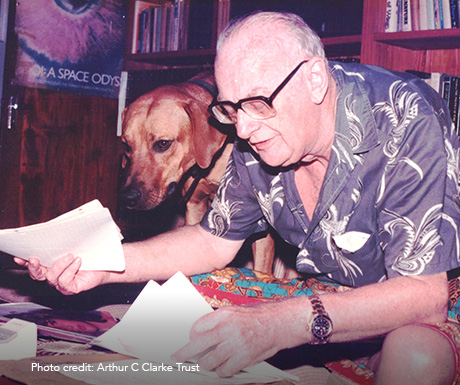

The writing and public speaking styles emerged from who he was as a person. He took his work very seriously – but never himself. That made it easy and fun for us to work with him. He had the curiosity of a ten year old right up to his 90th year. He was full of ideas and enthusiasm. On a practical level, he was an easy going man who had a great sense of humour.

Beneath that jovial self, however, lay a razor sharp mind and a neatly organised memory. One of my tasks was to verify various facts and references he quoted from memory, and more often than not I found that he had got it exactly right.

Despite having a good memory, he didn’t want to rely on it. He believed in documenting everything – taking copious notes, keeping records, and maintaining a good filing system (both physically, and in later years, digitally). “Don’t take chances with memory – it is stored in a fragile medium that degenerates after a while,” he used to say.

Sir Arthur was also a very determined writer. An accident (or polio?) left him semi-paralysed for several weeks in 1962, and as he slowly regained his control, he wrote a science fiction novel for juvenile readers: Dolphin Island (1963). The manuscript was mostly scribbled by pencil on a hospital bed (it was a few months before he could type again).

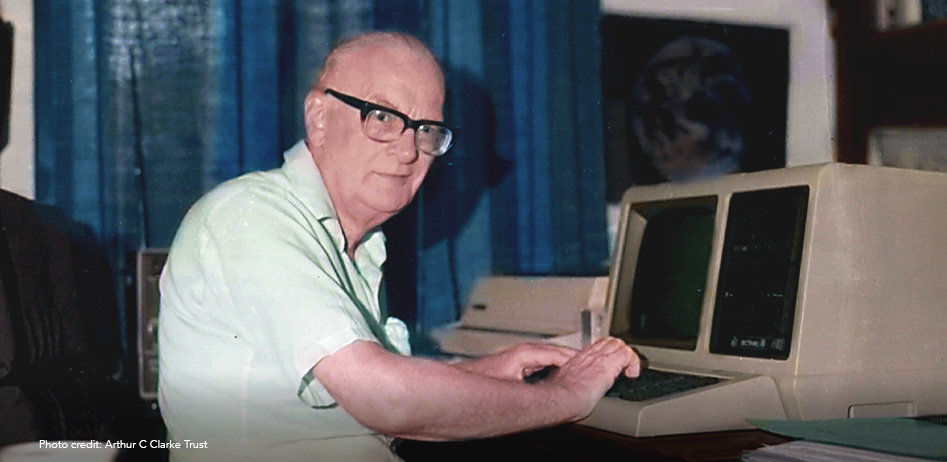

Sir Arthur was 70 when I started working with him, and he still typed all his fiction and most of his non-fiction essays himself; only correspondence was dictated. After he passed 80, he found it increasingly hard to type and had to reluctantly give up the tool of his trade. He tried dictation software but at that time (late 1990s) they were not sophisticated enough.

By that time, Post-Polio Syndrome had confined him to a wheelchair, and he had ended his globe-trotting. He was such an optimist that he turned his plight into an advantage. “Being confined to a wheelchair is actually a good thing – I can stay in one place and do all my writing, reading and imagining,” he said.

His mind stayed creative and agile to the end. The last time we worked together on a draft was in December 2007, when he reflected on his ’90 orbits around the Sun’ in a video message of nine minutes. He was frail but resolute and even upbeat at times. As I later wrote, that turned out to be his fond farewell to millions of fans.

Remember me as a writer, he said in that final message. Yes, we will.

See also:

Arthur C Clarke’s World of 2012: Insights from his Titanic Novel: Nalaka Gunawardene recalls the process of Arthur C Clarke researching and writing The Ghost from the Grand Banks (1990)